by Sarah S. Willen

In Israel, as in the United States, children have become pawns in government efforts to expel migrants -- despite clear evidence that arresting, detaining, and deporting children violates their human rights and has long-term traumatic effects. Policies like these demand our swift, strong, and emphatic condemnation.

“We’ve lost our minds,” 80-year-old Holocaust survivor Shalom Janakh said through tears in a short video condemning Israel’s move to deport children born to unauthorized migrant parents. Janakh’s beloved young neighbors, 9-year-old Michael and 5-year-old Shira, were recently arrested and detained by the Israeli immigration authorities along with their mother, Ishora, who came to Israel from Nepal to work as a caregiver. “This is a shame and a disgrace,” Janakh choked in his heart-rending appeal to Israeli Minister of Interior Aryeh Dery and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. “In my opinion, there should be a 6- or 7- meter wall with the Minister of Interior inside, not these children.”

Large Hebrew banner reads, “Don’t deport children.” Smaller sign reads, “Why do you want to deport me?” Source: United Children of Israel.

A 12-year-old student had similar things to say about the detention of her friend Mika, also 12, who was born in Israel to Filipino parents. Like other families targeted for deportation, Mika was arrested at home along with her 9-year-old sister, Maureen, and their parents, Sheila and Randy. “What kind of people are we that we’re deporting children?” Mika’s friend asked in a television interview, clearly aware of the weight of her words. “What kind of people have we become? We ourselves were strangers in other countries, and now we’re deporting foreigners from our country?”

Left: Twelve- year-old Mika and her family at their court hearing. Right: A letter from Mika, in Hebrew, in which she describes her family’s arrest and subsequent detention as “the most frightening thing that’s happened to me in my entire life.” Sources: Oren Ziv for ActiveStills (left) [1] and United Children of Israel (right).

Sheila and Randy came to Israel 25 years ago, like 60,000 of their conationals, with visas permitting them to work as caregivers for elderly Israelis. All of their children were born in Israel and, till now, educated in Israeli public schools. In August, families like theirs became targets of a deportation campaign launched just before the new school year that began on September 1 -- and in the political vacuum preceding the upcoming elections on September 17. As it has in the past, Israel’s right-wing leadership is trying to deport vulnerable migrants in an effort to re-assert sovereignty and curry favor with their political base. And once again -- as in early 2018, when Netanyahu tried to deport asylum seekers from Eritrea and Sudan, and failed -- a growing group of Israelis are fighting back.

In recent weeks, thousands of Israelis -- schoolchildren and educators, famous artists and former government officials, mental health professionals and Holocaust survivors like Shalom Janakh -- have made a clear demand of their government: Stop arresting migrant parents and their Israeli children. These Hebrew-speaking children, they insist -- who attend Israeli schools, celebrate Israeli holidays, and often want to perform the same military service required of their peers -- are Israeli “in every way.” Parent associations at a dozen different public schools have led efforts to prevent their deportation. Private attorneys have represented families in court. And new groups have emerged to strategize and lend support.

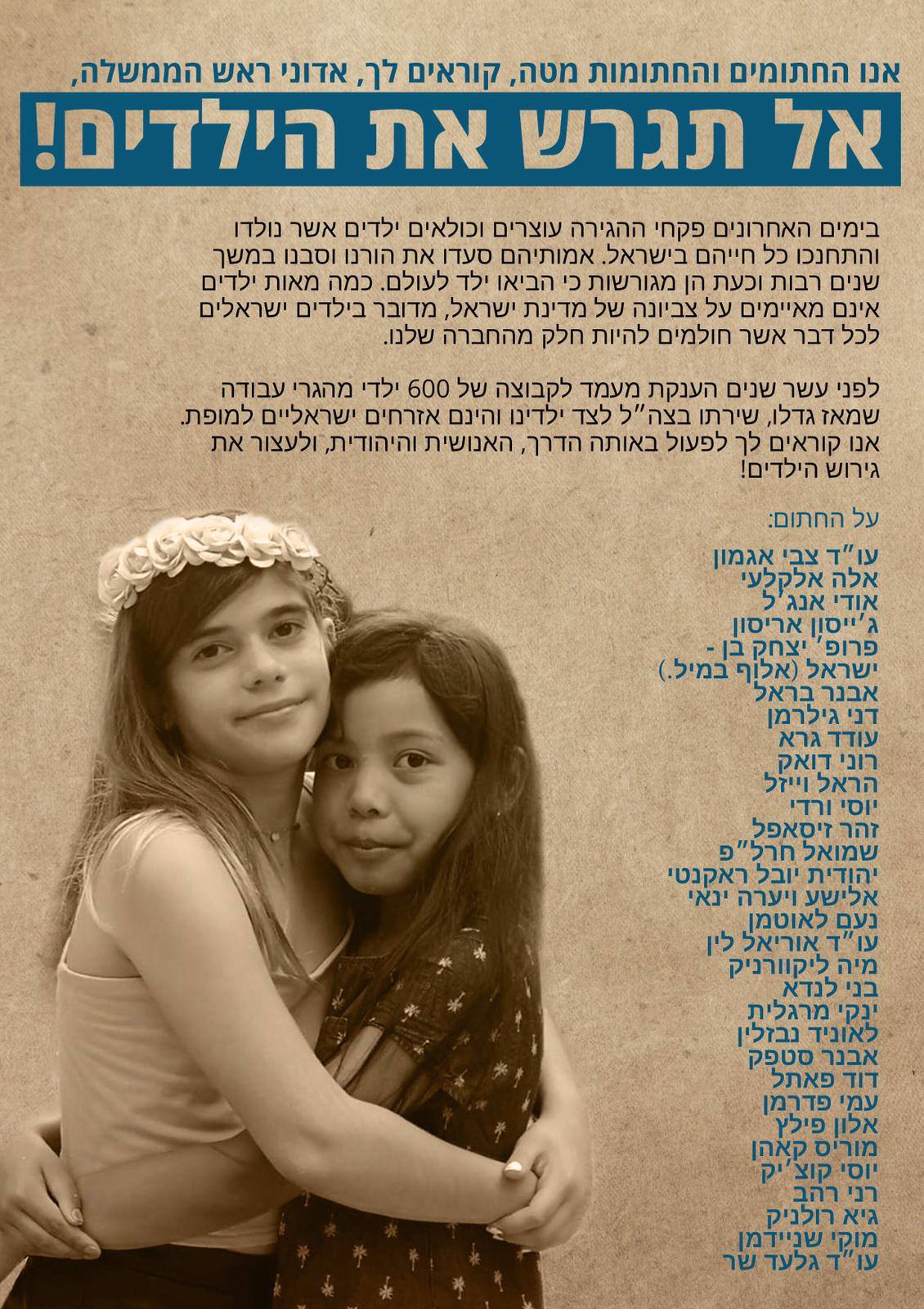

One of several petitions from prominent Israelis. Maureen is pictured on the right, together with a friend from Balfour Elementary School in Tel Aviv. The title: “Don’t deport the children!” Source: United Children of Israel.

Mika, Maureen, and their parents were detained for eleven days and nights. The girls’ friends, their families, and their broader community rallied in their support -- at demonstrations and in TV interviews, on social media and outside Givon Prison where they were detained until they were released on bond, pending appeal.

Supporters fear that the fate of Mika and Maureen -- or Shalom Janakh’s young neighbors, Michael and Shira -- could parallel that of families like 13-year-old Rohan and his mother, Rosemary, who were deported to Manila in August. An Israeli journalist who visited Rohan and Rosemary a few days after their expulsion painted a devastating portrait of the deportation and its traumatic impact on both mother and son. Rohan, struggling to understand why he had been cut off from the world he knew, put it this way: “My dreams are shattered.”

In my work as an anthropologist, I’ve spent a good deal of time with women like Sheila and Rosemary -- women who came to Israel in search of work opportunity, and eventually became pregnant. I first started meeting new migrant moms and moms-to-be in 2000, while laying the groundwork for the book, Fighting for Dignity: Migrant Lives on Israel’s Margins.

For a few of the women I got to know, pregnancy was planned and eagerly anticipated. But for many -- especially for women from the Philippines -- it was not. Unlike most of the migrant workers who came to Israel in the late 1990s and early 2000s, nearly all Filipinos arrived with legal authorization. The Israeli authorities defined pregnancy as “incompatible” with the arduous and underpaid work of 24/6 caregiving, so authorized migrant workers who became pregnant in that period automatically lost their legal status -- and often their jobs. (Since then, the law has changed: now migrant women who give birth must leave Israel within three months of their baby’s birth -- or send the child to the Philippines to be raised by relatives.) For these migrant women, an unplanned pregnancy can destroy their plans and dreams for the future.

Israel has no birthright citizenship provision. Neither can adult migrants become naturalized, even if they have lived and worked in Israel for decades. For the most part, only people with a bureaucratically legible tie to the Jewish people, or to an individual Israeli citizen (i.e., through marriage), can become citizens themselves.

The current deportation campaign is not the first time Israel has moved to round up and expel unauthorized migrants. In 2002, as I describe in Fighting for Dignity, the Israeli government launched a mass deportation campaign of unprecedented size and scale that wrought havoc on Tel Aviv’s newly established communities of global migrants and, within three short years, led to their collapse. What is new, however, is the state’s eagerness to deport children and families. Twice since 2005, Israel threatened to deport kids -- but in each case, plans ground to a halt, largely in response to intensive activist effort. On both of those occasions, small groups of children were granted permanent residency and their families temporary status. If these children serve in the Israeli army, which is mandatory for Jewish citizens, they can even obtain citizenship and their immediate families can receive permanent residency.

This time, however, things are different. Children like Maureen and Mika are being arrested, detained, and in some cases deported from the only country they know. Like Rohan, they are in danger of being expelled to a place they have never visited, far from their friends and teachers, where they may not speak the language -- and where no one will speak the lingua franca of their everyday lives, the colorful, slang-filled Hebrew of Israeli schoolchildren.

Holocaust survivor Shalom Janakh, whose young neighbors Michael (9) and Shira (5) were arrested along with their mother and are currently detained. Janakh described Israel’s new policy of deporting families as “a shame and a disgrace.” Source: United Children of Israel.

We don’t need sophisticated science to understand that arrest, detention, and deportation can traumatize children, with far-reaching effects. But for those who want data, the science is clear and strong. Last week, a group of Israeli mental health professionals consolidated the evidence in a position paper that details how “Arrest, detention, and deportation of children is a clear and serious danger to their mental health and future development.” These experienced clinicians acknowledge that children of migrants already belong to a vulnerable community, and that the stress of arrest, detention, and deportation has clear traumatic potential. They warn of severe consequences, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and behavioral disorders. They note that organizations of health and mental health professionals, in Israel and around the world, staunchly oppose the deportation of children -- and that children facing deportation would be unlikely to get the care they need, especially given their particular linguistic and cultural needs.

Meanwhile, more evidence of how deportation campaigns harm health is mounting on the other side of the Atlantic. Just last week, two social scientists published a New York Times op-ed opposing the detention of children in the U.S. under very different circumstances, but for similar reasons. Their conclusion is equally clear: “No detention center is safe and healthy for children.”

There’s plenty of room for disagreement about what fair and just immigration policies would look like. But deliberately traumatizing children is wrong. Policies that violate children’s rights and impugn their dignity -- whether in Israel, the U.S., or anywhere else -- demand our swift, strong, and emphatic condemnation. We live in deeply troubling times, and we cannot afford to lose our minds, or our moral compass.

[1] For one-time use, not for archive use.

Sarah S. Willen, PhD, MPH is Associate Professor of Anthropology and Director of the Research Program on Global Health and Human Rights at the University of Connecticut, USA. She is editor of Transnational Migration to Israel in Global Comparative Context (Lexington Books, 2007) and author of the newly published Fighting for Dignity: Migrant Lives at Israel’s Margins (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).