By Breanne Grace and Benjamin Roth

In the summer of 2014, the American media fixated on the US-Mexico border and the children and youth who were detained while trying to enter the US without the accompaniment of a parent or guardian. [Here we refer to these young people as unaccompanied migrant youth.] The media narratives were dehumanizing. Questioning the immigrants’ status as children and their legitimacy as human beings, these narratives drew upon intersecting and contradictory social constructions of children and childhood (James & Prout, 2015; Cunningham, 2006) and immigration status (Johnson, 1996).

Constructed as inagentive beings, migrant youth are often portrayed as lacking the capacity to migrate across international borders on their own accord and as unquestionably innocent and deserving. Yet at the same time, immigrants without legal status are often constructed as fully agentive and viewed as intentionally undermining the rule of law through their very presence. Their personhood becomes categorized as “illegal.”

Migrant youth uniquely occupy the conceptual space between these competing social constructions.

As a result, media portrayals of migrant youth at the border question youths’ status as children, the legitimacy of their independent migration, and their personhood. As Daniel Cook has noted, the childhood of these migrants becomes a “battleground” for what constitutes belonging:

“Standing for what they are thought to bring—their Otherness—the futurity of [unaccompanied migrant youth] became cast as neither hopeful nor legitimate. […] It is a threat that they might…maybe…perhaps…become us”

While there has been academic blog coverage of the media’s response to the border, these competing constructions impact far more than news coverage. Indeed, the contradictions embedded within these constructions are also institutionalized. In what follows, we discuss the ways in which this process is manifest in the services the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) designs to support unaccompanied migrant youth after they are released to their families and await deportation proceedings.

Federal law requires ORR to place unaccompanied migrant youth in the “least restrictive” environment while they undergo deportation proceedings. Some are placed in licensed residential facilities or long-term foster care, but the majority is placed with relatives or family friends living in the U.S. Among the latter, a small percentage—less than 15 percent—receives post-release services (PRS). PRS are case management services provided to migrant youth who are identified in detention as vulnerable and in need of additional support while they await deportation proceedings. The goal of PRS is social integration: these services include referrals to health care providers, assistance enrolling in school, help identifying legal representation, and referrals to mental health services. While sub-contracted case managers are able to refer children to these services, they are not guaranteed any sort of insurance coverage or financial assistance to facilitate access to services. What’s more, not accessing these services may be counted against migrant youth as they navigate court proceedings. Thus, although the goal of PRS is social integration, the process is essentially facilitated by the reality of removal: it occurs alongside the young person’s legal proceedings, and case managers are charged with observing children and ensuring court compliance. The contradictions within PRS—the push for integration while awaiting deportation; identifying psychological, medical, and social needs, but not providing resources to actually address these needs—reflect the “battleground” of these dueling constructions.

The goal of this blog post is not to provide a comprehensive overview of this social issue. Rather, drawing on a study we recently conducted of PRS, we hope to highlight two important themes where the tension between the constructions of child and undocumented immigrant arise.

VULNERABILITY

Media Portrayal of “Child” from the Associated Press/ Santa Fe New Mexican

In qualifying for PRS, migrant youth are explicitly identified as “vulnerable” and in need of support, yet no material support is provided. Case managers are only charged with telling youth and their families where they might and should find such support. Our research findings suggest that this is problematic throughout all service areas, but can be especially so for children’s access to legal representation. Many of the youth we interviewed were categorized as vulnerable based on criteria that could potentially be used as evidence of humanitarian legal claims. That is, someone within detention identified that these youth had experienced trafficking or persecution and that these experiences left lasting psychological, social, or medical needs. Yet despite this identified need, applications for humanitarian relief were not initiated and case managers and migrant youth still had to search out qualified legal representation upon release, often at significant expense to their sponsors. For some migrant youth, no such legal representation existed. The lack of legal services was particularly evident in “new immigrant destination” areas (Massey, 2008)—places such as suburbs and the American southeast that have not been home to new immigrants for generations. Despite their need for highly specialized legal services, these young people were often without legal options or were required to drive hours (sometimes into neighboring states) in search of services.

Despite their identified need and the additional support provided through PRS, not all migrant youth in our study were able to access services, risking refoulement. Thus, while their categorization of vulnerability and identification for services was based on a recognition that deportation would endanger the child, the process for deportation moved forward, putting the financial, social, and emotional burden for finding legal representation on the child and his or her family. This was in spite of their age, lack of resources, and identified trauma. This raises questions concerning the experience of migrant youth who do not receive PRS. Are they able to more easily access legal service providers and other local resources without the assistance of a case manager? And what is the role of the family—or sponsor—in helping migrant youth adapt to their new (if potentially temporary) home? Unfortunately, without data to answer these questions, the longer-term well-being of migrant youth is largely left to speculation.

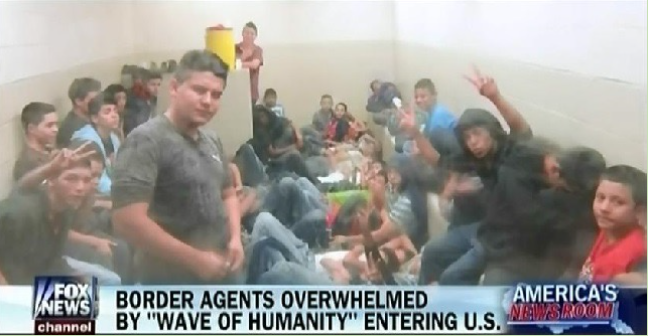

Media Portrayal of “Undocumented” from Fox News Screen Shot via Media Matters

While the UNHCR approaches such situations from a protection perspective, the young people processed for PRS were primarily dealt with in terms of their undocumented status. A 2015 report by the United States Government Accountability Office details how Customs and Border Protection (CBP) failed to identify legitimate humanitarian claims for young people: CBP officers were inadequately trained on the importance and criteria of humanitarian claims and these processes; current processing policies were incorrectly or inadequately implemented; agents were not trained regarding the rights and independent decision capacity of children; and agents were inconsistent in recognizing “legitimate fear” components and trafficking protections (12-35). This is notably different from UNHCR protocols that are established to ensure legal access without lengthy deportation processes. “Unaccompanied children” are further complicated in the U.S. because they are part of a larger mixed-migration process. Mixed migration movements, where refugees often move with non-refugees, are common, and the UNHCR has established protocols for processing in these circumstances. Yet despite the U.S. government’s ability to identify children’s humanitarian claims as a grounds for PRS, there are systematic obstacles inhibiting legitimate claims-making, the most severe of which is the U.S. government’s unwillingness to recognize its own categorizations of vulnerability, the lack of training for officers who make initial determinations, and an unwillingness to re-categorize this as a mixed-migration process.

SOCIAL INTEGRATION WHILE AWAITING DEPORTATION

In our research, case managers were often hyper-aware of their charge to help migrant youth socially integrate, even though these children could ultimately be deported. Case managers helped them enroll in school, join extracurricular activities, and develop meaningful connections in the U.S. Yet despite case managers’ best efforts, the migrant youth we interviewed still recognized that the lives that they were establishing in the U.S. could be short term. At best, migrant youth are able to develop meaningful—if temporary—connections to family and community and to successfully plead their case in Immigration Court. At worst, their integration is limited by the government’s contradictory effort to connect them to local supports and simultaneously extract them from the communities where these supports are located. Unless they are able to find affordable legal representation, the latter outcome is more common.

The version of childhood that migrant youth are expected to engage in is universalizing; it fails to recognize variation within life stage, economic conditions, and psychological pressures related to immigration status. Nonetheless, signaling one’s status as a “worthy child” remains important for the legal process. As children, migrant youth are expected to engage in the activities of childhood—attending school, establishing friendships, and engaging in extracurricular activities—but because of documentation status, these activities are understood as potentially fleeting, often undermining a child’s desire to engage in social life. Engaging in this prescribed childhood becomes both the definition of social integration for migrant youth and a coerced objective to meet in order to build a stronger legal case. Of course, establishing friendships and engaging in school is often even harder for young immigrants, as hard because they these individuals have the added burden of constant fear. We find that youth fear that their status might be discovered by their friends, or fear to dream about the future because the present is so uncertain.

For the migrant youth we interviewed who had previously worked or maintained households prior to migration, this new definition of the life course is met with mixed emotions. These young people often feel limited by the culturally-bounded expectations that they attend school and return to a childhood with minimal responsibility. However, they also recognize the burden their legal fees and medical bills contribute to household expenses. They often want—and need—to work to help their families and to have a chance at legal relief.

The politicization of immigration (especially undocumented migration) has led to contradictory services and implementation of services for migrant youth. Until policy makers address the social and political assumptions that are embedded in discourse about migrant youth, policy implementation will continue to undermine policy objectives. If the goal is social integration, migrant youth should be provided with reprieve from deportation in order to engage in their new communities. If the government has identified young people for additional services based on humanitarian need, then why are the same children being put at risk for refoulement? If children are identified as having pressing medical, social, or psychological needs that need to met, then why aren’t resources provided so that children and their sponsors can adequately address these critical needs?

Breanne Grace, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the College of Social Work at the University of South Carolina. Trained as a sociologist, Grace’s work focuses on African refugee populations resettled in the United States and Tanzania, as well as transnational family and community relations between resettlement sites, country of origin, and refugee camps. Her work focuses on social citizenship rights access after refugee resettlement and the political economy of humanitarian aid.

Benjamin Roth, PhD, is an Assistant Professor at the College of Social Work at the University of South Carolina. His research interests include the social, cultural, economic, and political processes of immigrant integration; the effects of legal status on youth development; and the geography of poverty and access to the social services safety net. His current projects explore how factors such as place and space, legal status, discrimination, social boundaries, and organizations (including schools, churches, and social service agencies) influence the adaptation of low-income immigrant youth and families.

Read more about Bre and Ben’s collaborative work at www.immigrantaccessproject.org

i. Children and youth who maintain no lawful immigration status the U.S. without authorization and who are apprehended without a parent or guardian are legally categorized as “unaccompanied alien children.” However, throughout this blog post we will refer to them as migrant youth. Their average age is 14.5 years old.

ii. It is important to note that this problem is not unique to the US. Currently the European Union and Australia are dealing with similar questions around asylum and refugee status. The situation of unaccompanied children differs in that young people are fleeing their countries of origin to the US, which is the first safe country of arrival.

Works Cited

Cook, D. T. (2015). A politics of becoming: When ‘child’ is not enough. Childhood, 22(1), 3-5.

Cunningham, H. (2012). The invention of childhood. Random House.

James, A., & Prout, A. (Eds.). (2015). Constructing and reconstructing childhood: Contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood. Routledge.

Johnson, K. R. (1996). " Aliens" and the US Immigration Laws: The Social and Legal Construction of Nonpersons. The University of Miami Inter-American Law Review, 263-292.

Massey, D. S. (Ed.). (2008). New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage Foundation.