by Angélica Mejía

(English translation below. For additional posts in this series, visit: "Migration and Belonging.")

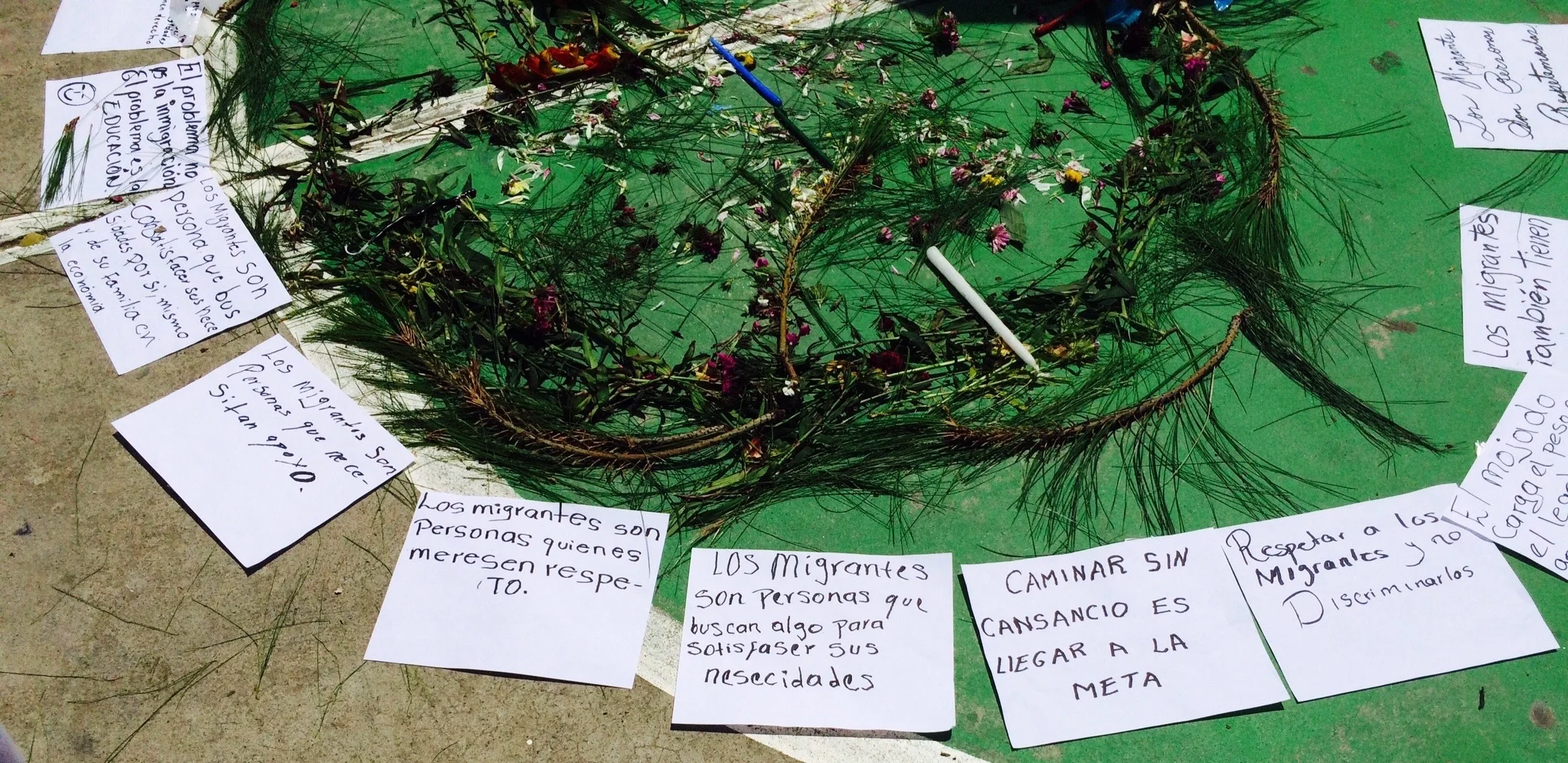

Actividad escolar. Créditos fotográficos: Lauren Heidbrink

La falta de cuidados parentales es un problema que afecta a un número significativo de niños y adolescentes en Guatemala. De acuerdo al informe de la Red Latinoamericana de Acogimiento Familiar (RELAF) (2010), más que 5,600 niños están institucionalizados en Guatemala, muchos de quienes experimentan inseguridad considerable mientras están transferido a través de orfanatos e instituciones por el país. Las razones por la ausencia de cuidado parental son diversas--como una alta prevalencia de enfermedades crónicas, pobreza extrema, el conflicto armado, un legado de la violencia a migración significante que pueden resultar a la desintegración familiar. Estos factores deben ser entendidos necesariamente como factores relacionados entre sí en lugar de entender como factores individuales o aislados que resultan en la pérdida de cuidados parentales.

Si bien las estadísticas son alarmantes, es importante reconocer cómo algunos niños y jóvenes sin el cuidado parental desarrollan la resiliencia. Al analizar cómo los jóvenes se emprenden proyectos de vida, tales como la búsqueda de educación formal y vocacional, así como sus fuentes de motivación, podemos empezar a desarrollar las instituciones y programas que inspiran más que impiden su desarrollo.

A través de mi colaboración desde 2007 con varias organizaciones comunitarias, he llegado a trabajar con 29 jóvenes, varios de los cuales encarnan condiciones de desigualdad y abandono al tiempo que demuestra al mismo tiempo la resistencia y la fuerza a pesar de estas condiciones. A pesar de encontrar algunos orfanatos e instituciones que disuaden a niños a partir de continuar su educación o el aprendizaje de las competencias profesionales, es decir, otras organizaciones sociales promueven el desarrollo personal y ofrecen importantes recursos educativos. Los que recibieron el apoyo y la oportunidad han terminado el ciclo de primaria, básico y bachillerato; algunos iniciaron una carrera en la universidad.

Actividad escolar. Créditos fotográficos: Angélica Mejía

Tal es la experiencia de Marcos(1), 17 años de edad en su último año de bachillerato y sus hermanos menores, Mercedes de 15 años de edad y Dario de 13 años de edad. Son becarios de la Fundación Portales de Esperanza, ellos lograron continuar su educación, recibir apoyo de una organización comunitaria, y sobreponerse ante las circunstancias socio-económicas. Otros han optado por estudiar en escuelas vocacionales—carpintería, cocina y mecánica—para lograr un empleo que les permita contribuir con sus familias.

En mi colaboración durante la última década con las instituciones y organizaciones que sirven a los jóvenes sin cuidados parentales, los jóvenes articulan varias fuentes de resiliencia—de un deseo de continuar su educación, a contribuir al sustento de su familia, a la creencia en su propio potencial, a un deseo para controlar sus propias condiciones y futuros. Aun cuando estamos a menudo rápidos alabar a organizaciones no gubernamentales, fundaciones privadas e iglesias de distintas religiones para "salvar" a los niños y niñas necesitados, hay que señalar que los propios niños y niñas demuestran la resistencia en la identificación y la búsqueda de oportunidades dentro de estas redes sociales.

La identificación de las fuentes de la resistencia interna de los jóvenes es crítica. También lo importante es apoyar a las instituciones estatales, sociedad civil, y los sectores privados que reconocen y fomentan la capacidad de niños y niñas de recuperación. Sólo por crear oportunidades para que la población infantil participe de manera significativa en estas conversaciones, que podamos satisfacer las necesidades de los niños y niñas sin cuidados parentales.

Bibliografía:

Informe situación de la niñez sin cuidado parental o en riesgo de perderlo en América Latina (2010). Contextos, causas y respuestas. Guatemala: Red Latinoamericana de Acogimiento Familiar.

Mejía, Angélica. (2014) Tesis: “Orientación, metodología para la atención escolar de los niños huérfanos”

Angélica Mejía (Angie) cumplió una Maestría en Gestión Social para el Desarrollo Local de la Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Guatemala (FLACSO-Guatemala) y cuenta con estudios de licenciatura en administración de organizaciones educativas de la Universidad San Pablo de Guatemala. Ella ha trabajado en diversas organizaciones educativas con enfoque social en organizaciones locales principalmente atendiendo a la niñez en orfandad.

(1) Seudónimo.

Resilience of Youth Without Parental Care

School activity. Photo credits: Lauren Heidbrink

The lack of parental care is a significant challenge confronting a growing number of young people in Guatemala. According to Red Latinoamericana de Acogimiento Familiar (RELAF) (2010), over 5,600 children are institutionalized in Guatemala, many of whom experience considerable uncertainty as they are routinely transferred between orphanages and institutions throughout the country. The reasons for an absence of parental care are diverse—from a high prevalence of chronic illnesses to extreme poverty to armed conflict to a legacy of violence to significant out-migration that may lead to family disintegration. These factors must necessarily be understood as interrelated rather than individual or isolated factors leading to loss of parental care.

While the statistics are alarming, it is important to recognize how some of the children and youth without parental care develop resiliency. By analyzing how young people undertake life projects, such as the pursuit of formal or vocational schooling, as well as their sources of motivation, we may begin to develop institutions and program that inspire rather than impede their growth.

Through my collaboration with several community-based organizations since 2007, I have been able to work with 29 young people, several of whom embody conditions of inequality and abandonment while simultaneously demonstrating resilience and strength in spite of these challenges. While I have encountered some orphanages and institutions that dissuade children from continuing their education or learning vocational skills, that is to say, other social organizations promote personal development and offer important educational resources. Those receiving support and opportunity have finished primary, middle and high school; some are pursuing a college education.

School activity. Photo credits: Angélica Mejía

Take the experiences of Marcos(1), a 17-year-old in his last year of high school, and his younger siblings, 15-year-old Mercedes and 13-year-old Dario. With scholarships from the Fundación Portales de Esperanza, they have been able to pursue their education, receive support from a local organization, and begin to overcome difficult socioeconomic circumstances. Still others pursue vocational training—carpentry, culinary and mechanical—eventually securing employment to contribute much needed financial resources to their families.

In my decades’-long collaboration with institutions and organizations serving young people absent parental care, youth articulate varied sources of resilience—from a desire to pursue education, to contributing to their family’s livelihood, to a belief in their own potential, to a desire to control their own conditions and futures. While we are often quick to laud non-governmental organizations, private foundations, and churches for “saving” young people in need, it should be noted that young people themselves demonstrate resilience in identifying and pursuing opportunities within these social networks.

Identifying the sources of young people’s internal resilience is critical. So too is supporting state institutions, civil society, and the private sector that recognize and nurture their resilience. Only by creating opportunities for youth to meaningfully participate in these conversations, may we meet the needs of young people without parental care.

Works Cited

Informe situación de la niñez sin cuidado parental o en riesgo de perderlo en América Latina (2010). Contextos, causas y respuestas. Guatemala: Red Latinoamericana de Acogimiento Familiar.

Mejía, Angélica. (2014) Tesis: “Orientación, metodología para la atención escolar de los niños huérfanos”

Angélica Mejía (Angie) graduated with a Masters in Social Management of Local Development from Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Guatemala (FLACSO-Guatemala) and has a bachelor’s degree in Administration of Educational Organization from Universidad San Pablo of Guatemala. She has worked at various educational organizations with social focus on local organizations principally serving orphaned children.

[1] Pseudonyms.

For the previous blog in the series: Ramona Elizabeth Pérez Romero: El Papel de las Comadronas de Almolonga/The Role of Midwives in Almolonga

For the next blog in the series: Celeste Sánchez, Giovanni Batz, Lauren Heidbrink, and Michele Statz: A Conversation on Translation/Una Conversación sobre Traducción