By Neha Tummalapalli

The movement of unaccompanied minors along the Southern border of the United States has increased exponentially in the last decade. The primary federal entity responsible for the care and custody of unaccompanied children in the United States is the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), which places children within one of 200 subcontracted shelters typically run by nonprofit organizations. If ORR’s operational capacity, or bed space in licensed facilities, exceeds 85% occupancy for 3 days, it becomes categorized as an influx period. During these periods of increased immigration, the detention process changes. Instead, ORR enlists unconventional structures, such as convention centers, military bases, and “soft-sided” facilities, to house children for extended periods of time.

This visual research illustrates three case studies of new types of facilities for unaccompanied youth in Texas. Emergency intake sites and influx care facilities are operated by ORR, while central processing centers are run by US Customs and Border Protection (CBP). These temporary, often quickly constructed emergency facilities are bound to fewer legal standards such as the Flores Settlement Agreement and blur the roles of the involved agencies, often leading to harmful conditions and poor treatment of children (Zak 2021).

Case Study I: Fort Bliss Emergency Intake Site

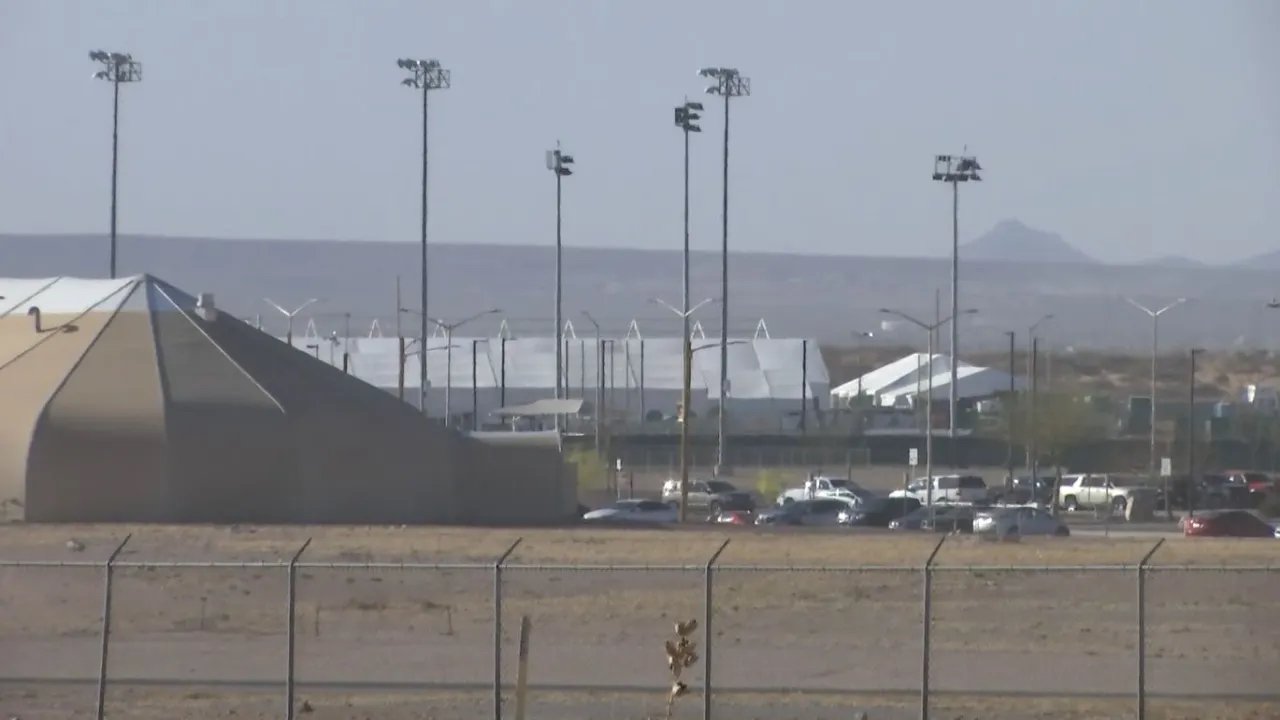

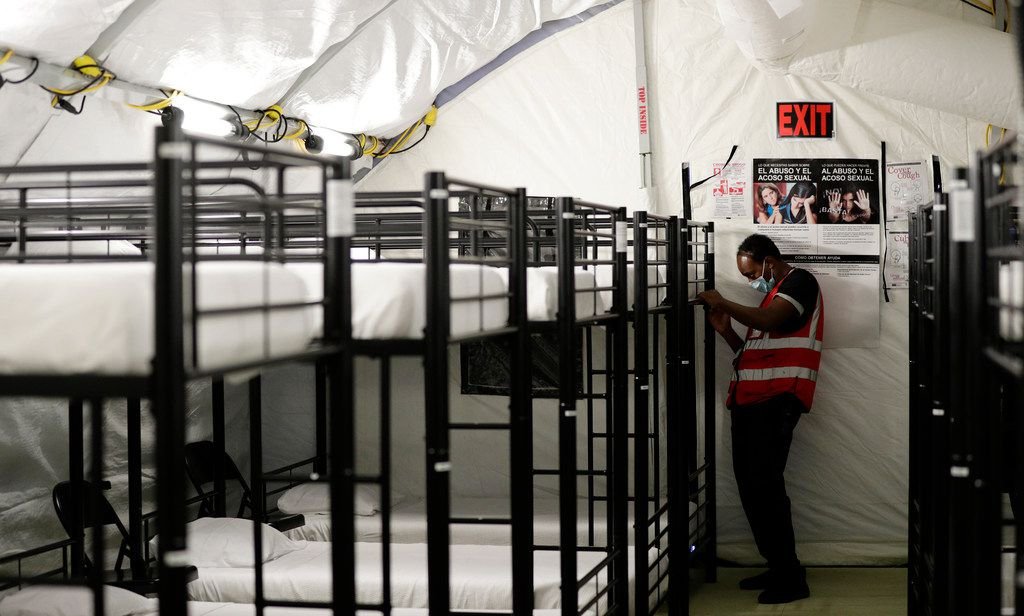

On March 25, 2021, the US Department of Health and Human Services announced that Fort Bliss would open an Emergency Intake Site for unaccompanied children. The military base in Texas had the potential capacity of 5,000 beds (Ortiz 2021). At the peak of arrivals of migrant children in April and May of 2021, the facility housed over 5,518 boys and girls 13-17 years old. Fort Bliss is considered a temporary, “soft-sided shelter,” which means it is a tent structure made of vinyl fabric. This type of facility is vulnerable to extreme weather, such as the desert sandstorms, extreme heat waves, and more recent record-breaking rainfall. The tents are not weather-proofed, meaning there is no sealant applied to the bottom of the tents (Kladzyk 2021). As a result, there is a space at the bottom of the tent where sand and rain can enter.

Since media coverage of the facility is so limited, aerial images revealing the overall organization of the complex are difficult to find. One report identified 12 tents with several hundred migrant children in each, while another claimed there were 5-6 soccer field sized tents that housed up to 1,000 migrants per tent (Andersson 2021; Villagran 2021). The City of El Paso denied public information requests for construction documents which would have revealed more about the shelter layout. The city explained that Fort Bliss is under federal jurisdiction because it is a military base. In either case, the accounts of staff and released migrants confirm that the facility was very crowded. There were not enough clothes and showers for young people, which left many children showering less than once a week. The government initially contracted out caregiving responsibilities to Chenega Corp, but Chenega Corp subsequently transferred care to an independently owned and operated Servpro franchise in late May. Servpro is a disaster recovery and clean-up company, whose workers are not trained in youth care (Villagran 2021). There was minimal transparency in the vetting process for the workers, and conditions in the shelter rapidly deteriorated. In June, employees and advocates were so concerned about children in Fort Bliss harming themselves that employees banned the use of pens, pencils, scissors, nail cutters, toothbrushes, earrings, and the metal clips in N95 masks (Montoya-Galvez 2021). Because family reunification services were limited, the length of stay for children in the facility was prolonged. Given the poor quality of care, the mental health of many children reportedly became dire.

Case Study II: Carrizo Springs Influx Care Facility

The influx care facility in Carrizo Springs, located two hours southwest of San Antonio, was first opened in late June of 2019. It was used for a month and then kept on hold until February 22, 2021. It accommodates up to 1,120 children ages 2 to 17 in hard-sided structures. It consists of 8 buildings that have bedrooms in 14 suites with each suite housing 8 children. Another building consists of 2 wings which can serve 28 children each or be reserved for medical isolations. The dorms are separated by gender, with a separate space for tender-aged children under the age of 13 (Health and Human Services: Carrizo Springs). Like other influx care facilities, emergency intake sites and central processing centers, Carrizo Springs is not a licensed facility, and HHS itself has conceded that it exceeds licensing standards. Based on the limited imagery of the facility, there does not appear to be educational and recreational services provided for migrants (Hudson and Martin 2021). There remain no public accounts of staff or young people that describe the conditions of the Carrizo Springs facility, and public information requests for construction documents and building inspection reports submitted to the city of Carrizo Springs were ignored. An official in the Dimmit County Planning Department even claimed to not know about an influx care facility in Carrizo Springs on the phone. The available information about this facility suggests that it is relatively more equipped to care for migrants than other emergency facilities. However, most of the information about this facility comes from the Health and Human Services website, so it is hard to gauge the actual conditions without any accounts from young people or staff.

Case Study III: Donna I Central Processing Center

The third case study is Donna I in Donna, Texas. In contrast to influx and emergency intake facilities, this central processing center is run by CBP. Opened on February 9, 2021, this is another soft-sided facility and had an initial maximum capacity of 500 beds during the pandemic. Since March of 2021, the occupancy has ranged from 2,200 to 4,500 individuals. The showers were designed for an occupancy of 1,000 resulting in many children reporting that they did not shower for days at a time (Andersson and Laurent 2021). The facility is organized into 8 pods which are further divided by clear vinyl into smaller units (Spagat and Merchant 2021). Since Donna I has far surpassed its occupancy limits, there are often no spaces between sleeping mats. The spaces dedicated to recreational and educational activities are also fully taken over by sleeping mats. There is no consistent recreation time, although officials claim to host recreational activities during the cleaning of the pods. Donna I has two medical teams which consist of a nurse practitioner, medical assistants, and emergency medical technicians (Ordin 2021). They conduct health intake interviews and screen for any symptoms of COVID-19 or other diseases. The number of deployed medical teams has not kept pace with the rapid overcrowding in the facility and arrivals of groups of 200 or more children at a time during influx periods. In early April of 2021, Court appointed medical expert Dr. Paul Wise visited the Donna facility and found that 500 children below the age of 12 had been at the facility for over one week in violation of the Flores Settlement Agreement which stipulates children should be released from CBP custody within 72 hours of apprehension (Ordin 2021). The severe overcrowding at this facility has made it unmanageable for CBP to implement and enforce any welfare standards. The crowded spaces have also led to rampant spread of COVID-19, lice, and other communicable illnesses.

Conclusion

These case studies reveal how the spatial qualities of the facilities significantly impact the care young people receive. The temporary tent facilities often cause spaces to be uncomfortable and unsafe due to lack of weatherproofing and privacy. Young migrants further suffer when the facilities operate over the maximum capacity. They often receive insufficient medical and legal services, and the cramped spaces lead to children contracting illnesses. While these three examples occurred during the Spring of 2021 and circumstances have since improved, it is important to study these conditions as they will likely repeat in the next influx of migrant children. For example, after advocates criticized CBP for the conditions at the McAllen central processing center which opened in 2018, similar issues have been observed again in the Donna I facility two years later. There is significantly less oversight and regulation for these unlicensed emergency shelters, which makes young people even more susceptible to the poor conditions. Furthermore, the dearth of accessible information and visitors to these facilities makes it challenging for the public to hold ORR and CBP accountable for their treatment of migrant children and youth.

Works Cited

Health and Human Services. Carrizo Springs. February 17, 2022.

Jenny Lisette Flores et al v. Janet Reno, CV 85-4544-RJK. (C.D. Cal. 1997).

Office of Refugee Resettlement, Children Entering the United States Unaccompanied: Section 7 Policies for Influx Care Facilities, September 2019.

Office of Refugee Resettlement, Unaccompanied Children Program, April 2021.

Ordin, Andrea S. Independent Monitor Report for Jenny Lisette Flores et al v. Merrick B. Garland. Case No CV 85-4544-DM, (C.D. Cal. April 2021)

Texas Health and Human Services Commission, Minimum Standards for General Residential Operations, April 2022.

About the author

Neha Tummalapalli is a fifth-year undergraduate honors student at Syracuse University pursuing a bachelor's in architecture with minors in policy studies and data analytics. She is passionate about exploring the intersections of architecture with socio-political issues to understand the implications of complex spaces. She has been involved in diverse research investigations throughout her undergraduate career, which has shaped her perspective on architecture. Her research work has been financially supported by the Syracuse University SOURCE award.