by Sophia Rodriguez

In this piece, migrant newcomers reflect a conflicting narrative of home and (un)home, and of belonging and (un)belonging in Hartford, Connecticut. This project involves an asset-based program at Hartford Public Library that is specifically tailored to increase newcomer migrant youth belonging utilizing the library as a safe space amid hostile political times and unwelcoming city and school environments. The library space has social significance. It is both an alternative to newcomers’ experiences of being othered in school and directly deepens their educational knowledge and belonging.

Caption: Welcome quilt the newcomers made in October of 2017, Hartford Public Library. Photo credits: Sophia Rodriguez

Hartford has long been a destination for immigrants. Recently, patterns of immigration have changed, bringing newcomers from increasingly varied home countries and an increased number of undocumented, unaccompanied, and refugee youths into the high schools. Newcomers may arrive in Hartford’s schools with limited education in their own countries or interrupted schooling because of their refugee or displaced statuses. Many have experienced trauma, such as adjusting to reunification with their families after long separations or leaving family members behind. Some have come from war-torn countries or from communities where they experienced severe deprivation, violence, or a constant threat of violence.

Currently, Hartford newcomers represent 31 native languages, with the largest groups speaking Spanish, Karen, and Arabic languages, and have been in the country for less than 30 months. Additionally, the minoritized population in Hartford Public Schools has increased; in the wake of Hurricane Maria in 2017, a significant number of high school-age students (over 130) arrived to Hartford from Puerto Rico. Connecticut also has the largest gap in achievement in the country between its English learners and their English-speaking peers. More specifically, Hartford receives the majority of language learners in the state. In Hartford, schools struggle to support newcomers due, in large part, to decades of assimilationist and “English only” approaches to immigrant incorporation (Peguero, Bondy, & Hong, 2017). To address the newcomers’ needs, the Hartford public library has partnered with the school district to provide a unique program to increase newcomer belonging, data from which this post draws.

Home and belonging

Participating newcomers originate from Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Peru, Syria, Rwanda, Guinea, Togo, Tanzania, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, and Cote d’ Ivoire. Many express conflicted feelings about where “home” is and what it means, especially because some escaped violence, civil strife, and extreme poverty. Newcomers’ responses to the question, “What does home mean to you?” include the following themes: united with family, a safe place, and places [they/I] can’t go back.

Art project: What is community? Photo credits: Sophia Rodriguez

From these responses, many youths commented on how learning English and being a new arrival presents many challenges for them even in the Hartford community and in their schools. Interviews and focus groups reveal feelings of belonging and (un)belonging, and specifically how schools are contested spaces—and how the library with its asset-based programming has become a safe space. Youth commented on their shared struggles as newcomers in school, how the library space was “different,” and how they felt a sense of belonging because of their shared solidarity of being different. Many youths connected with each other out of necessity because they reported feeling ostracized at school by teachers and peers.

When asked how the library-based program was different than school, a Togolese youth explained: “It’s like school, but not really. We can express ourselves. In school, it’s testing, memorizing, English only, rules. We don’t speak English well. It’s embarrassing. Here, all students are new immigrants, and no one will laugh at you.”

Reasons for this comfort varied. A Dominican youth shared how she feels the library allows her to express herself and be more “social,” noting, “We are all English learners.” A Togolese youth explained, “We come here to escape the poverty and violence but are still struggling here. We get made fun of for our English.” A Burundian youth commented, “Teachers ignore us or think we can’t talk about anything. Sometimes, I don’t say anything in school.” In response to feeling as though school focuses on testing rather than the student, a youth reported, “It’s better here [library] because we can know each other. We are all new.”

In the library program, youth learn about civic engagement and leadership in their schools and communities. Newcomers explained how the curriculum increased their belonging. A youth articulated, “We designed a project for other newcomers like us to help them when they arrived so we can make the school better for kids. It was the best thing I ever did in my life. And, we translate it, too, into different languages since we have so many here. That’s how we become local leaders here.” This aim to become leaders is significant.

“‘We become leaders’ is the phrase most often heard from migrant youth who participate in the library program.”

To this point, youth recognized their uniqueness as newcomers and wanted to develop tools for other newcomers to facilitate belonging in school since the schools offered minimal support. Youth designed a digital library for newcomers that included tours of the school, how to navigate class schedules, descriptions of “what it’s like” to be at the high school. They also researched local community organizations that offer services for refugees and newcomer immigrants. They presented their projects in a “gallery walk” final presentation to library staff, teachers, parents of newcomers, and peers at the end of the program. Evidence suggests that newcomers benefitted from engaging in program curricular activities in ways that increased their belonging and relationships with others.

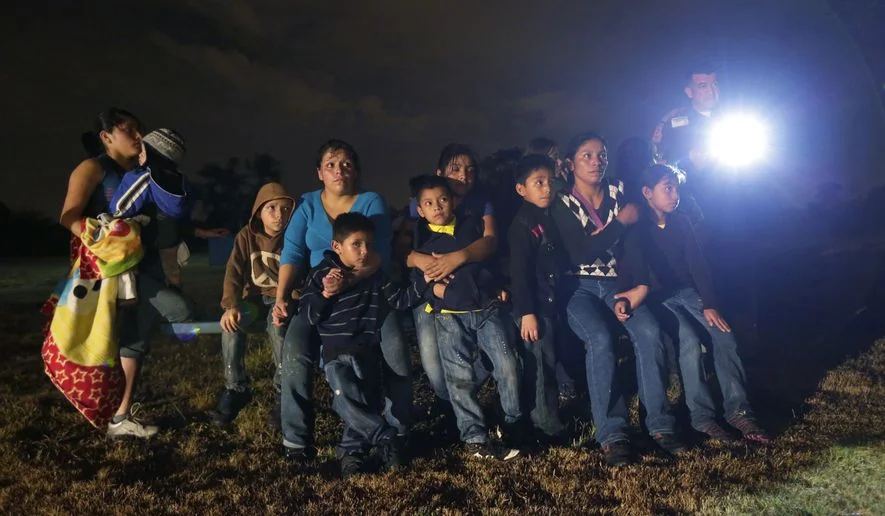

Newcomer from Togo explained, “People don't, like, get it. They don't get the pain. But, they also do, especially at school. I try to explain that I know English, and school says, ‘we gonna test today.’ and you have no choice. It’s like isolation.” (Photo from a story in the Connecticut Mirror about the program.)

Newcomers develop a sense of solidarity and belonging from participating in the library program. One youth shared, “Even if you come here [to the library], but you don't know that country where everyone is from, it’s ok. We are all in the same boat, not knowing English. You can be from anywhere and still belong here [at the library].” While newcomers expressed feelings of isolation at school, the library-based program created a space to cultivate a positive sense of self, relationships, a sense of civic awareness, and a desire for action. Developing a curriculum rooted in the strengths and knowledge of newcomers, the library program meaningfully cultivated belonging and integration for youth.

The data from this ongoing project suggests that a generative, rather than assimilationist, framework of belonging maintains the potential to meaningfully integrate newcomers. This library-program is indeed a promising practice.

Sophia Rodriguez is an Assistant Professor of Cultural Foundations at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her scholarship has appeared in the peer-reviewed journals Educational Policy, Education Policy Analysis Archives, Educational Studies, The Urban Review, and The Journal of Latinos and Education.