By Nellie Chu

In the mega-metropolis of Guangzhou in southern China, millions of migrant youths arrive in the city’s wholesale market for “fast fashion”—to try their luck at becoming bosses of their own labor. Ultimately, however, their participation in the fast-paced market heightens their sense of emotional and financial insecurity, even as they strive to achieve wealth and social mobility.

In the heart of Guangzhou, China, a multi-storied wholesale market for low-cost fast fashion towers above a line of low-lying buildings. Inside, thousands of stalls cram along narrow hallways. Fast fashion is the “just in time” delivery of trendy and low cost fashion garment and accessories. Transnational supply chains for fast fashion rely on informal labor practices and mass manufacture capabilities in regions across the Global South. Young migrant entrepreneurs operate these stalls, serving clients from Seoul, Moscow, Abu-Dhabi, Mexico City, and Singapore.

Amid this whirlwind of fast-paced buyers, roving carts, and changing styles, millions of hopeful young migrant women in their late teens and early twenties leave their families and homes in the rural regions of China’s interior provinces, such as Sichuan, Human, Guangxi, and Henan. They arrive in this fashion wholesale market in Guangzhou to start their businesses in the hopes of gaining access to the transnational economy of fashion. These women of the post-1980s generation have come of age after Deng Xiaoping’s introduction of market reforms in 1978. Since then, advertising campaigns and mass consumption of multinational brands and fashion luxury items in Chinese cities have spurred these female youths to aspire for femininity, cosmopolitanism, and urbanity as ideals of beauty and womanhood. In contrast to the images of the Iron Girls, symbolic of heavy industry and national strength during the Mao era, young women today disparage peasant livelihoods and factory work, which once served as sources of personal pride and class-based collectivity. Instead, migrant women of this generation strive to become entrepreneurs in the hopes of achieving financial autonomy and secure livelihoods.

With modest amounts of starting capital in hand, these migrants converge upon these market spaces to buy and sell mass volumes of low-cost fast fashions. Fueled by the circulation of foreign and domestic fashion magazines such as Marie-Claire, Vogue, and Cosmopolitan, as well as TV shows including Korean dramas and Gossip Girl, migrants borrow images from magazines or websites, and modify them according to what they imagine their consumers desire. Their self-professed claims to consumerist expertise lead them to aspire to become bosses of their own labor, despite limited prior knowledge about design, garment construction, and merchandising. They scour the Internet and exchange ideas through blogs, creating virtual platforms via Wechat, Taobao, and other social media upon which they can expand their clientele. Inspired by the aura of glamour and style, they ascribe beauty and style as conduits of experimentation, and use fashion as an outlet to achieve their dreams of financial independence.

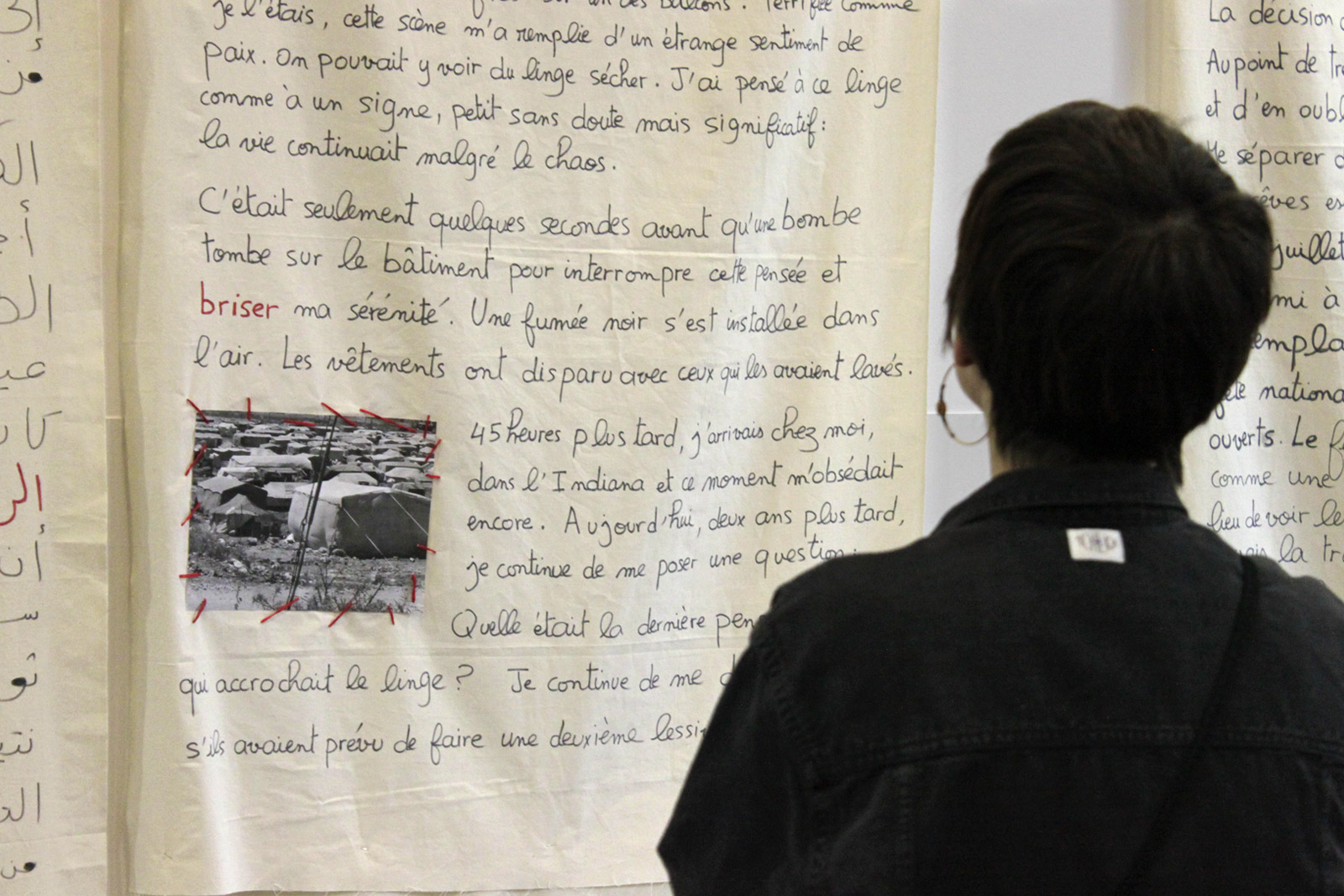

Sample image of a social media platform featuring fast fashion garments and accessories in China.

Sample image of a social media platform featuring fast fashion garments and accessories in China.

Their stories are part of a larger anthropological project that I have conducted since 2010. My ethnographic project follows the lives of Chinese, South Korean, and West African migrants in Guangzhou, who labor to become worldy citizens through their experiences of entrepreneurship. I trace the rhythms of anticipation among these intermediary agents as they move in and out of factories spaces, showrooms, boutiques, and warehouses. Through techniques of participant observation and semi-structured interviews, I show how the global supply chains for fast fashion are forged by the continuous de-linking and re-linking of class and labor mobility across trans-regional and temporal scales.

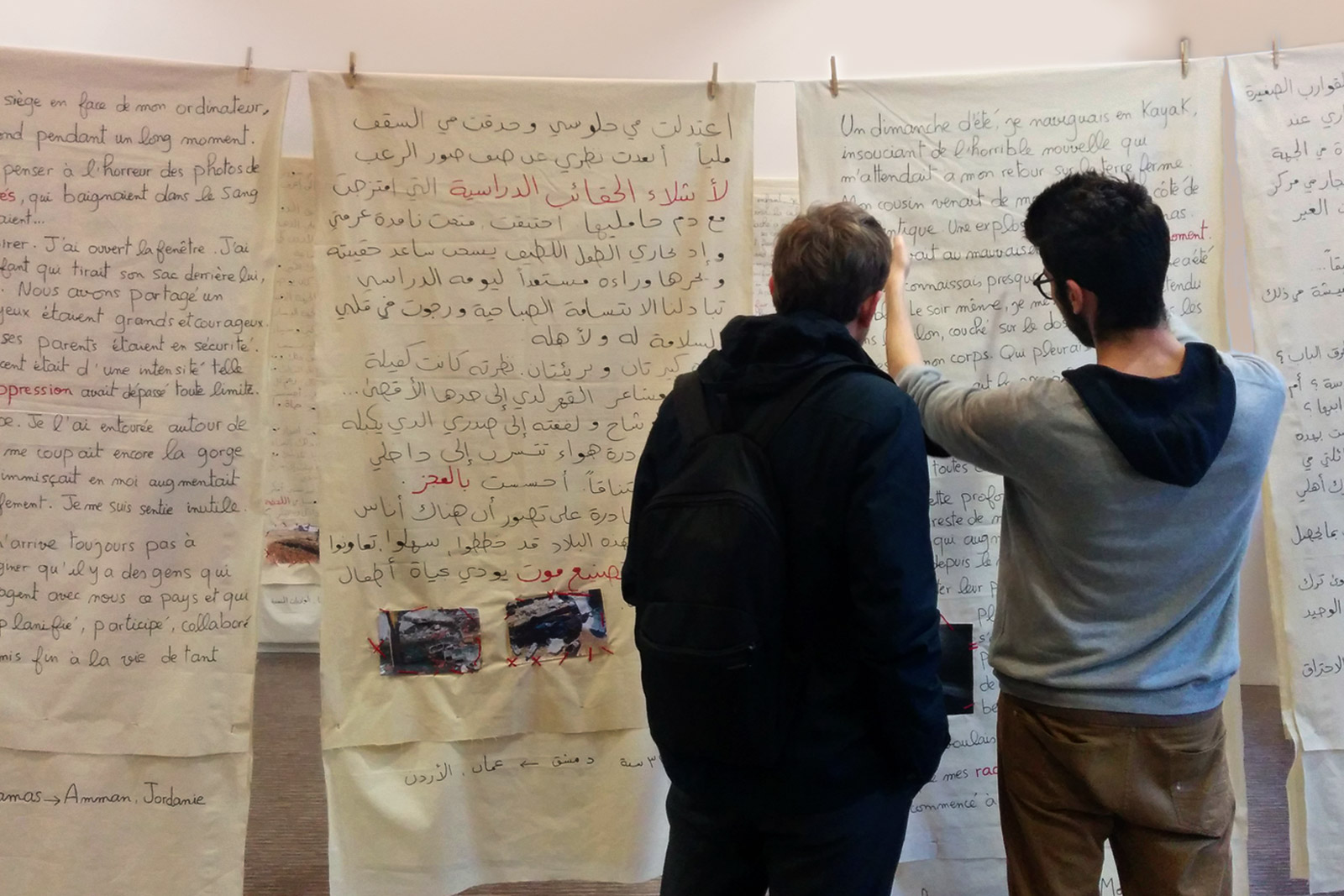

A narrow hallway lined by fashion showrooms in Guangzhou’s wholesale market for trendy, low-cost garments and accessories. Photo credits: Nellie Chu

Despite their aspirations for economic self-reliance, individualistic expression, and social mobility, many of these Chinese women desire a future that remains intimately tied to familial relationships as well as to gendered norms with respect to romantic love, marriage, and motherhood. Indeed, the majority of small-scale businesses in garment wholesale and manufacture within Guangzhou’s fast fashion niche involve partnerships with married couples in the form of shared labor or a mutual pooling of investment capital. Young, unmarried women co-invest with their parents, siblings, close friends, or other unmarried partners. Many youths claim a combination of personal independence, self-fulfillment, and family honor as the primary motivations for engaging in their risky business ventures. Such claims are well-documented by other anthropologists and observers of China, including Lisa Rofel and Sylvia J. Yanagisako; Xia Zhang; Minhua Ling; and Jeroen de Kloet and Anthony Fung. In fact, the topic of migrant entrepreneurship has been endorsed and celebrated in popular culture through soap operas, including Legend of Entrepreneurship (Wenzhou Yi Jia Ren) on Chinese state-sponsored television. Through their everyday work lives in the fast fashion sector, migrant youths learn to negotiate their personal aspirations for economic self-reliance with the business of marriage, family, and motherhood.

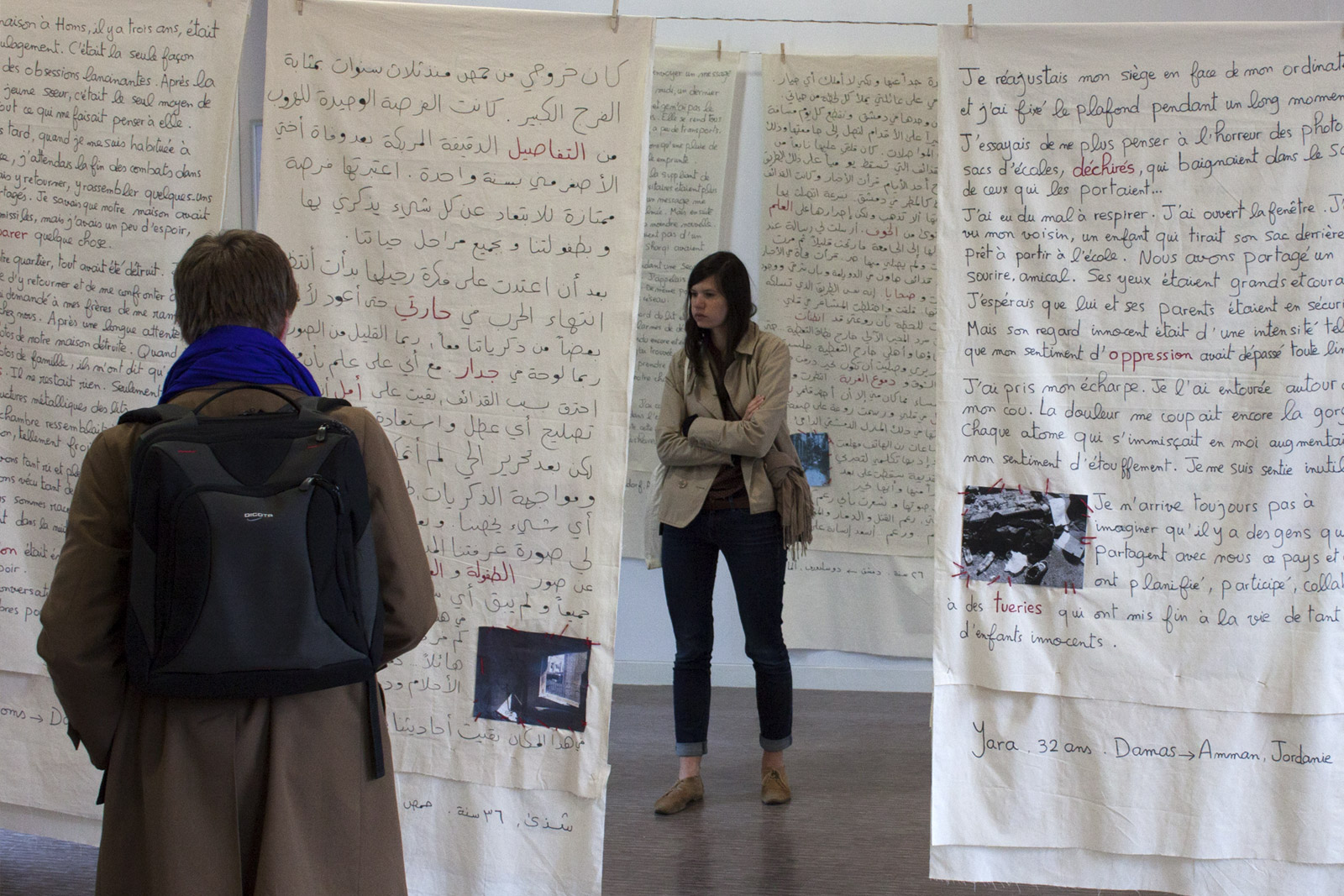

A migrant saleswoman and a model stand among a crowd of eager onlookers as they anxiously juggle several transactions at a time. Photo credits: Nellie Chu

For example, Anna, a 23-year-old migrant woman from Dongbei, operated a highly successful teeshirt wholesale business in the market in 2011. As our friendship deepened, she recounted how she gained a foothold in Guangzhou’s fashion wholesale industry as a young teenager a decade earlier. Anna began laboring as a wage-worker in a shoe factory in Dongbei, which was operated by a Sichuanese businessman. After she had proven to the boss her willingness to work, she encouraged him to enroll her in a shoe design program in Sichuan. She stated, “When I requested this from my boss, I promised him that I would improve his business. And I did. Initially, he had no idea that I had so much drive and ambition. He merely saw me as a young girl – innocent and unmotivated. He didn’t know that I had a tireless ambition.”

Anna spent several months in the design program before leaving Dongbei for Guangzhou. At that time, transnational migrants from Korea, Japan, and Nigeria swarmed upon the fashion scene in Guangzhou in order to establish trading and manufacturing networks. As a newly arrived migrant, Anna fell in love an older Korean businessman who operated a shoe wholesale outlet near the railway station in the eastern part of the city. Their romance lasted for about eight years, during which Anna learned and perfected the skills necessary for running her own fashion wholesale business. Their relationship, however, was eventually mired by distrust and even jealousy between them. She elaborated,

Over the years, I had saved up vast amounts of money from our business without his knowledge. I did this because I had to support my parents and me. I knew that he never believed in me…that I could possibly out-succeed him. The years that I had saved up money on my own, he would spend it all away. After our relationship ended, I used my money to start my own business. Years later, after he realized that I had become more successful than he, he begged for me to return to him. At that point, it was too late.

Anna’s rise to entrepreneurial success as a young migrant woman involved a romantic and business partnership with her former lover. Her narrative impressed me not only because of the incredible drive and persistence she displayed as she strove to accomplish her entrepreneurial dreams, but also because of the subtle power dynamics that underlie her encounters with businessmen in positions of authority. Fully aware of her relatively vulnerable position as a young woman, she followed in these men’s footsteps in order to gain the skills and knowledge necessary for running a fashion enterprise. She knew, however, that to out compete them, she had to emotionally distance herself from them.

Anna’s story reveals the entanglements of entrepreneurial risk and intimate desires, particularly among couples who share the responsibilities of running their own businesses. In China, the risks of losing one’s business are almost as certain as the risks of failed marriages and relationships. The highly competitive business environment in Guangzhou, where profits among small-scale businesses quickly come and go, heightens the sense of emotional and financial insecurity that market participants face in their efforts to achieve wealth and financial independence. In Anna’s case, struggling migrant entrepreneurs like herself sometimes cannot differentiate between business competitors and collaborators. Furthermore, these tensions reveal underlying gender inequalities. Bonds of trust with powerful men are thus difficult to bridge and sustain among migrant women like Anna, who has spent most of her life struggling to achieve financial independence.

A young customer takes a break from the hustle that often characterizes this fashion market. Photo credits: Nellie Chu

Nellie Chu is an Assistant Professor of Cultural Anthropology at Duke Kunshan University in Kunshan, China. She has published in Chinoiresie, Modern Asian Studies, Culture, Theory, and Critique, and the Journal of Modern Craft.