The question ¿K'uxi elan avo'onton? invites us to reflect from the heart, because we are not only able to feel from the heart, we can also think from the heart. To respond honestly, I had to turn to that part of my inner self that I had neglected for so long—it was better to ignore the pain caused by the displacement I had endured throughout most of my life as a migrant. This question became an introspective process, one that made me realize I was unsure about how my heart was doing, or whether it was still intact. Had my heart really returned with me to Mexico or had a part of it stayed in Los Angeles, the place where I lived 20 years of my life before deportation?

The heart wants what it wants: Belonging schizophrenia

Despite my past, I am fortunate to have had the opportunity to experience life in environments that reconnected me to my roots and humble upbringing. I was born into a poor family. My parents came from rural towns with hardly any schooling, but they were hardworking people. When my time came to relocate for work and moved to Chiapas, a state with the highest rates of poverty in Mexico, I could see the similarities between it and my childhood home in Naulcapan, a municipality located in the State of Mexico. It was not foreign to me to live in towns that lacked sewer systems, or in a house with walls made of bricks and a roof laminated with thick carbon paper—the kind that would slowly start to fall apart and collapse during a hailstorm. Of course, the poverty and social exclusion from where I came was different from the kind that indigenous families in Chiapas endure. I never had to walk more than two hours to school. I never had to drop out of school to start working in the fields to support my family.

Returning to what resembled my pre-migration life was the consequence of being uprooted from my adopted country. Of all the places I have lived post-deportation, I have not found one that feels like home. Despite the encouraging words of friends who say, “welcome to your country,” or “welcome home,” my heart knows: I am not home.

In the past seven years, I have lived in seven cities and three countries, places where I have felt a kind of belonging schizophrenia. Part of me wants to belong, but another fails to do so. Even with the support networks and friends I have made, I can’t entertain the idea of living in any of those places for the rest of my life. I manage to physically move into each new space, but my emotional self never fully occupies it. What is the point of decorating my new “home” if the displacement I carry with me continues to persist? Could I ever attach myself to a place the way I did as an L.A. transplant?

These contradictory emotions forced me to admit there is something wrong with my heart. Even with the passage of time, the scars and the pain are still there. I am not the same person after undergoing the dehumanization of deportation, something only those who have experienced it can understand. At this point, I can only ponder what will make my heart whole again. The answer has yet to reveal itself; hopefully at some point I will know. In the meantime, my heart urges me to keep looking—and not only for a sense of home, but also a political family to which to belong. Finding the latter proves just as difficult.

Searching for home in “advocacy”

The moment in which I came out of the shadows of deportation also marked the start of my search for a place to belong in advocacy. The trigger for my post-deportation activist trajectory was the announcement of the DACA program by the former President Barack Obama in 2012. It began as a hopeful journey, but soon enough I experienced the invisibility that arises when social movements also reproduce the oppression they denounce.

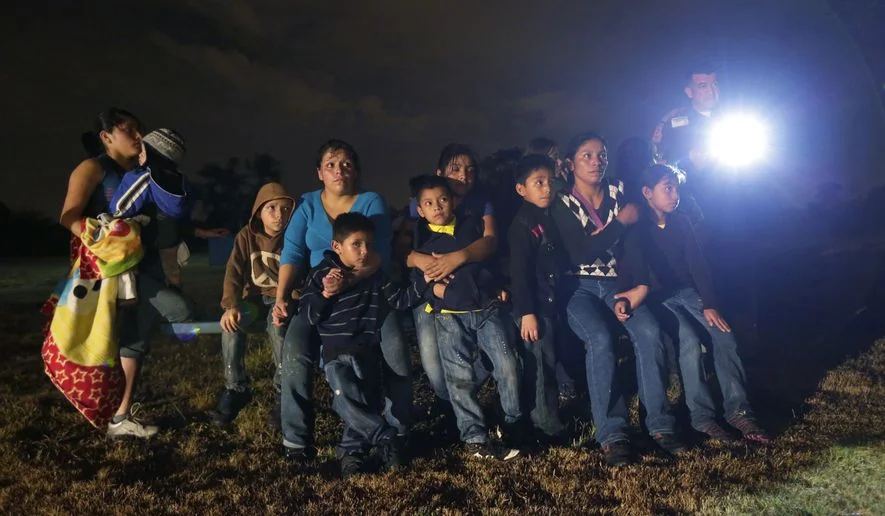

The immigrant rights discourse has created a hierarchy among us, selecting which migrants are “worthy” and deserve to be included, and who should be left out. In the U.S., those of us who have been deported belong in the latter category. In Mexico, we have been similarly ignored. It was not until recently that the political elite have begun to discuss return migration, in great part due to Donald Trump’s antagonism towards Mexico. Still, few have meaningfully discussed the deportations occurring during prior administrations, including Obama’s record-setting removals and the criminalization of immigrants as a result of the 1996 legislative changes to INA that took effect under Bill Clinton.

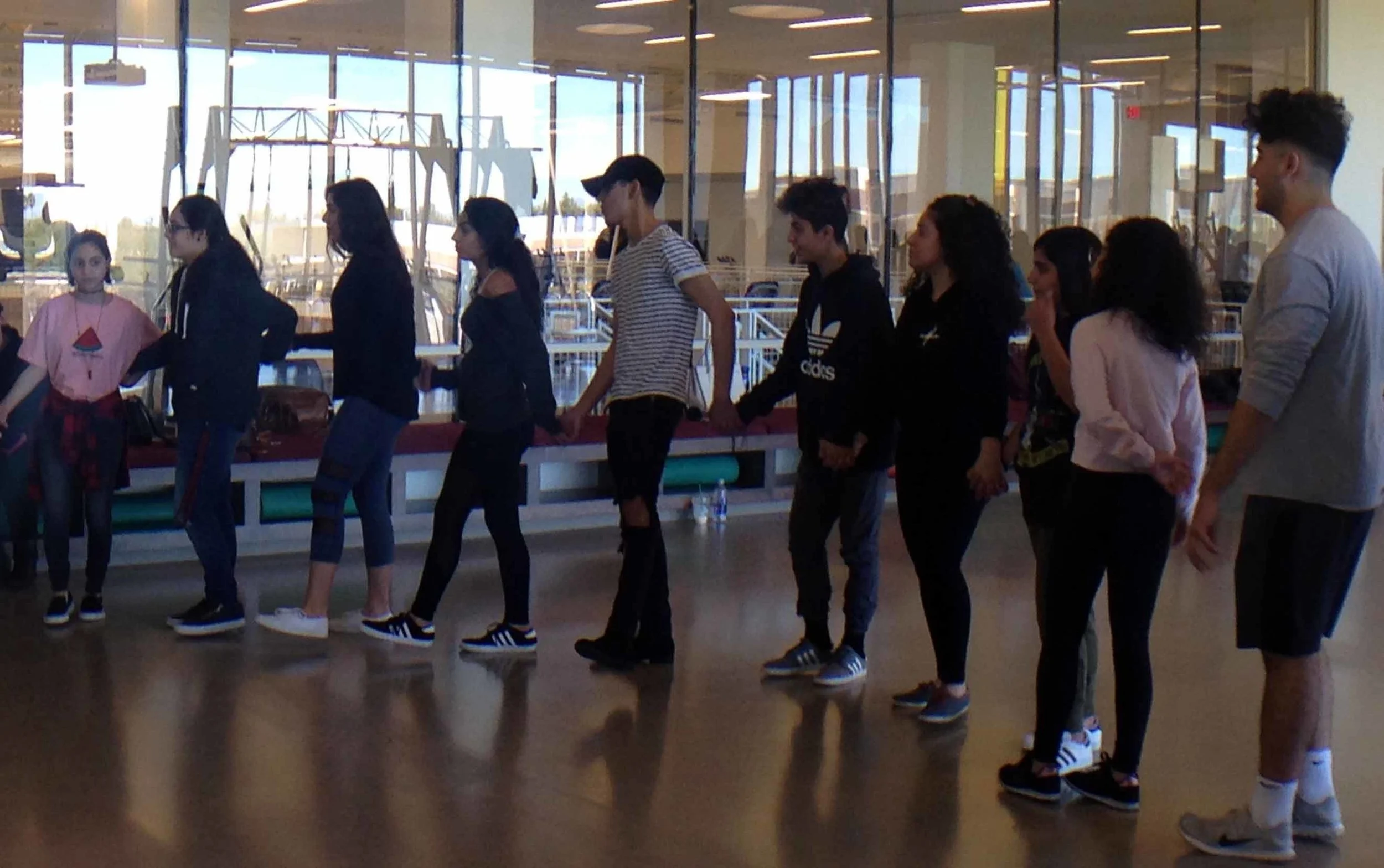

It has become more convenient for the Mexican government to seek the attention of those belonging to the “good immigrant” category. Following the initiation of DACA, the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Relations, Senators, universities, and high-level policy makers invited DACA Dreamer groups to (re)discover their cultural roots via tours of iconic places in Mexico City and the ancient Aztec ruins of Teotihuacan. Political actors attempted to convince us that they supported Mexican immigrants here and abroad. Yet, these educational trips designed to reconnect Dreamers were simply a public relations tool.

Dreamer tourism, as we termed it, has continued to grow over the past couple years. At the same time, there is no real interest in giving the “unwanted” deportee a platform to demand a dignified reinsertion in Mexico. Additionally, and in contrast to our U.S. immigrant counterparts, we don’t have a return ticket to the United States—not even a tourist visa to visit our former homes, the places and people we left behind. Having presented to these Dreamer delegations, I am left with a clear view of the many asymmetries that exist between us. They are platforms that lack the conditions for genuine dialogue about our struggles. And on the occasions when we have raised such concerns, we just become a nuisance: to the government institutions that sponsor the trips, to the nonprofit organizations that welcome such efforts, and to the activist DACA Dreamers who fail to see how they have legitimated our exclusion by accepting a reconnection with their “México lindo y querido”, the beloved Mexico to which they make no indication they would want to return permanently.

In these times, when migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers face an increasing hostile social and political environment here and around the world, we must have ongoing exchanges on how we contribute to the exclusion of others who are below us on the ladder of oppression. This is the introspection I find missing in U.S. immigrant advocacy movements—movements that understand social inclusion as stopping deportations, and that fail to consider the dark abyss one falls into after deportation.

If advocates measured their effectiveness based on reality, they would realize this failure is profoundly consequential. The culprits here are still anti-immigrant policies based in ignorance and xenophobia. And yet, immigrant activists must be accountable for not creating advocacy strategies that respond to the multidimensional and unjust realities created by deportations. This includes (1) family separation, where U.S. children are stripped away of their parents or forced to leave their U.S. homes to reunite with deported family members; (2) harsh treatment and penalties for deported immigrants, including re-entry bans; and (3) lack of reception programs to integrate deportees in the education system or the labor market in the countries receiving them.

These issues are just the tip of the deportation iceberg. Rather than yet another request to include “my story” in someone else’s research or advocacy campaign, I search for collaborations or co-creative efforts to unite our interconnected fights and struggles, not to be “educated” on my own intimate experiences of deportation, long before Trump assumed power.

I’m left asking: Does social justice have a time limit or does it expire under “new” political realities? Will deportations prior to Trump take a back seat to the somehow more “urgent” situation under the current administration? So long as new movements answer these questions affirmatively, then there is a dire need for a new paradigm for immigrant activism. We must learn to speak of struggles in ways that do not re-victimize those who have suffered or to render them invisible by privileging the “good immigrant” narratives.

Heading north to reclaim my own fight

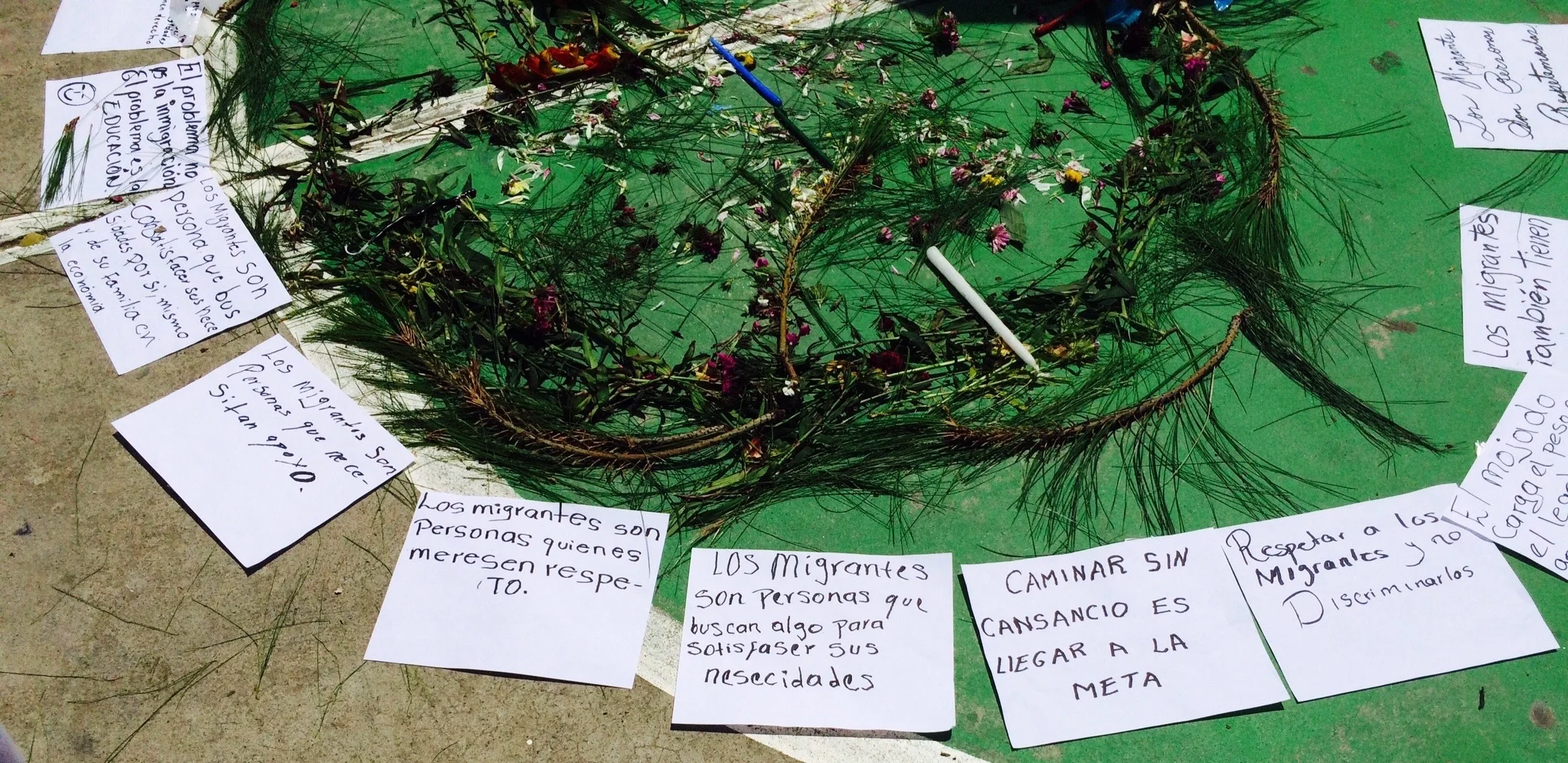

Today, I am back in Tijuana—and this time by choice. After years of chronic emotional burnout aggravated by those internal battles I had not anticipated, I am stronger. In the southern region of Mexico, I learned that there is an alternative perspective to activism—one that is designed from a collaborative and participatory approach. This work creates spaces of dialogue and reflection where migrants are the migration experts, the protagonists in all processes and organizing work. We are not just research subjects to be studied, or whose stories should be collected.

This takes decades to master, and in no way have I reached competency in it. At the same time, I am encouraged to engage on initiatives created by migrants, for migrants, and am filled with a sense of responsibility and the urgency as when I first started this journey. Seven years ago, it would have been impossible to engage in this type of work: I was putting back together the pieces of a shattered life. Yet the south has reenergized me to reclaim my own fight back north. You can’t be in a place like Chiapas, one that embodies the resistance of the country, without it changing you in some way. So, what comes next?

In 2009, the year of my deportation, there were between 300 to 400 of us arriving every day in Tijuana.[i] Today, that figure is slightly over a quarter of such deportation levels, with nearly 100 deportees arriving daily. With the anticipation of the continued expulsion of Mexicans from the U.S., there is still much work ahead.

The needs and demands of deportees: From reinsertion to family reunification